Increasing the SG costs much less than you think

- On 10/07/2019

- Superannuation Guarantee

System objectives

The Financial System Inquiry recommended an objective of superannuation, which has been accepted by the government, and is now pending legislation. The objective is “to provide income in retirement to substitute or supplement the Age Pension”.

The goal of the system is to provide an income in retirement that offers more dignity than the Age Pension alone. This is achieved through the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) system and by providing tax concessions for voluntary contributions, which together give most people the opportunity to become self-funded at least for part of their retirement.

At retirement, people will broadly fit into three groups; some people will be eligible to receive the full Age Pension immediately, some will become part pensioners, and some will be self-funded. Many will become full or part pensioners later in life as they use up their superannuation.

We should note that individual circumstances change throughout life and these groups are not always known until late in a member’s career. The national goal is to give more Australians the opportunity to become self-funded, at least for the early years of their retirement.

At the current rate of 9.5%, the SG will provide a dignified retirement for most people, warding off poverty (in conjunction with the Age Pension). However, it will not provide everyone with a reasonable replacement rate, nor a comfortable retirement. A higher SG improves the position for more people and has the advantage of also reducing long-term Age Pension costs.

Obfuscation of the facts

The Grattan Institute’s recent coverage of the Paper delivered last month by Michael Rice and Nathan Bonarius1 has been misleading. For example, Grattan has publicly stated that the Rice Warner modelling shows that there is no need to raise the level of mandatory superannuation (the SG) from the current level of 9.5%. This is consistent with Grattan’s public opinion, which is based on some basic analysis of medium-term impacts backed by a few cameos.

Since then, Grattan has come out with another sensational claim that raising the SG to 12% would cost average workers $30,000 each. In fact, its analysis has less to do with the SG level, but is more about the issues of means-testing of the Age Pension, which we have documented in detail and which will be described more fully in an Actuaries Institute Green Paper on retirement to be released in the next month.

Far from supporting Grattan’s long-standing hypothesis, our Paper concluded that a level of 10% to 15% was necessary to achieve the system objectives, including the reasonable one of making more people self-sufficient in retirement. In twisting our argument, Grattan also erroneously claimed that the Paper shows that we (at Rice Warner) believe increasing the SG would have huge fiscal costs not only in the short term but also in the long term2.

In the first instance, we should state that our Paper is independent and had no preconceived conclusions. The assumptions and parameters used were conservative. Any long-term analysis is sensitive to the assumptions and we were careful not to pick parameters that would distort the outcomes. For example, we discounted benefits during retirement at CPI rather than at wages and assumed retirement at age 67 despite the average retirement age presently being about age 63. This leads to a conservative or ‘idealised’ result. We tested in detail sensitivities around the assumptions we made as shown in the Paper.

Further, Grattan’s conclusion that superannuation comes at a net cost to the budget is wrong because it assumes that the measured tax concessions on a ‘revenue-foregone’ basis (now labelled ‘tax benchmark variations’ by Treasury) represent the cost of a change of policy to the Budget. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The aggregate tax concessions on a ‘revenue foregone’ basis is not the same as the ‘revenue gained/lost’ from a change in policy. They are a total system measure for a single year without comparing against an alternative counterfactual (would people spend the money, or would they save it elsewhere and in what form?). The measure doesn’t represent either a total system cost to compare against savings on the Age Pension nor a lifetime present value impact for a given person (see our worked example).

Increasing the SG has complex distributional impacts which aren’t captured by aggregate fiscal estimates in Treasury’s Budget analysis. Though large tax concessions are provided to those on high incomes, increasing the SG does less proportionately for the rich, as the SG is not paid on income above $221,080 a year and concessional contributions are capped (currently $25,000 a year). In addition, levels of voluntary savings at higher incomes will be partially substituted by an increased SG, resulting in a lower net increase in measured voluntary contributions for those on high incomes.

On the other hand, increasing the SG provides a boost to those on lower incomes with little (if any) tax concessions, though these people will still expect to receive an Age Pension. It could be argued that some people on very low incomes would prefer salary rather than the SG, but that could be achieved through improved benefits under the current tax and transfer system.

Those caught in the means test thresholds will benefit from tax concessions but may similarly miss out on some Age Pension benefits due to the operation of the means tests which needs review. In particular, the taper rate for the assets test should be lowered and consideration given to simplifying the means tests by having a single income test.

Measuring the impact of changes

In our paper, we warned specifically that these measures of system costs are inadequate. In particular, we highlighted three issues:

- Dependency on consistency in the benchmark (levels of personal tax rates).

- Difficulty of comparisons across time.

- Unrealised savings.

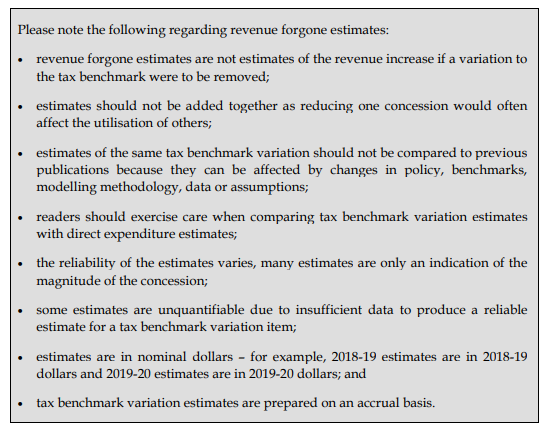

This is not to criticise Treasury. It provides its own list of health warnings (Figure 1) which are routinely ignored by some commentators.

The reality is much more complicated and, to our knowledge, no alternative analysis covering this issue adequately has been done to date. This is partly due to the short-term nature of Budget costings which only need to be done over the forward estimates (four years). See the worked example for an illustrated difference of Budget impacts and ‘revenue foregone’.

The alternative ‘revenue-gain’ measures calculated by Treasury are also not useful for this analysis as this is not a marginal measure and assumes that the money currently in superannuation through preservation rules and the compulsory nature of superannuation contributions will remain. This means the ‘revenue gain’ measures only partially capture behavioural effects which would be stronger relative to an increase in the SG.

The value of increasing the SG

Increasing superannuation can be a win for both Government and consumers if targeted appropriately. The increase of the SG to 12% will be beneficial for Australia in many ways:

- It builds our capital markets which can be beneficial for a nation which has an infrastructure backlog and a technology deficit.

- It reduces the cost of the Age Pension to close to 2% of GDP by the turn of the century, way below the levels in any other country – and providing scope to divert government expenditure to Aged Care and other areas of need.

- Professional management of pooled savings produces superior investment returns than might otherwise be achieved via private savings.

- It increases the quality of life for the majority of Australian retirees.

Grattan has forgotten the original reasons for introducing the SG and its original target level of 12%. In 1992 the then Treasurer John Dawkins provided a detailed document outlining the rationale for the new retirement incomes policy3. At the time, the policy was contrasted against the counterfactual of raising the Age Pension to 35% of AWE – the alternative policy required to provide a similar increase in after-tax retirement benefits (in aggregate).

This illustration is important, because increases to the SG provide value independent of savings to the Budget alone through the delivery of a higher living standard to all Australians. Without this context we are left with the proverbial position (Grattan’s?) of knowing the price of everything, but the value of nothing.

We recognise that there will need to be continual review of tax concessions and Age Pension eligibility to ensure fairness in the system, but this is relatively easy to do following each quinquennial Intergenerational Report.

Finally, Government and industry need a better metric of the cost of marginal changes to superannuation policy. This is necessary if we are to properly measure changes to the system and have an informed debate. The current widely used metrics represent a theoretical upper bound and understate the benefits of our system.

The fact is that increasing the SG costs much less than we think but delivers benefits to all Australians through strong real returns and enhanced retirement benefits and reduced reliance on social security systems.

Figure 1: Treasury caveats – Tax Benchmark Variations4

Worked example – ‘Revenue foregone vs. Impact to budget’

Say a middle-income person, aged 25 contributed $100 to superannuation through an increase to the SG and is on a marginal tax rate of 34.5% (32.5% bracket + 2% Medicare levy)5:

- The Government would lose $35 in marginal tax but gain $15 in tax on superannuation contributions in year 1. This provides a net $20 cost to the budget.

- The Government will now collect tax on investment earnings in superannuation every year, at say 9% (net of CGT discounts and franking credit refunds).

- Were the consumer not putting the money into superannuation, they would have likely spent the income. The RBA has estimated a marginal propensity to consume of over 100% for a similar tax cut6

- This is not accurately reflected by measuring the tax concessions on a revenue forgone approach which would assume that all future investment earnings should be taxed at marginal rates and would report an even higher cost to revenue than the initial $20 concession in year 1. The measured ‘revenue foregone’ would be $115 (in real terms) to retirement.

Eventually, over the years to retirement (67), the revenue collected from tax on investments will exceed the initial loss of tax to the Government. The net difference would be $50 in tax collected within superannuation vs. $35 in tax collected without it (discounted to today’s dollars). The Government actually benefits by $15 and the member has 2.3 times the initial investment available to spend in retirement (both in real terms).

The fact that these two figures (a $15 saving vs. a $115 cost to Government) don’t reconcile illustrates the issue with using ‘tax benchmark variations’ for evaluating policy changes. The point is underappreciated by most superannuation commentators.

Of course, there are instances where increasing the SG would be a real cost to Government (e.g. those who would otherwise invest outside superannuation, including those closer to retirement) and continued contributions over the person’s lifetime create another fiscal strain in year 2 – our analysis shows that a lifetime of contributions in this instance would come at a small benefit to Government after allowing for the impact on the Age Pension.

Our point is, however, that the change in measured tax benchmark variations represent an upper limit of what the cost of superannuation could be, and this simple analysis shows that increasing the SG for some individuals could be revenue positive/neutral in the long term through higher savings. Simultaneously the increase in superannuation will reduce Age Pension costs and increase retirement incomes through delivery of high real returns.

1 https://www.ricewarner.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Rpt-What-is-the-right-level-of-SG-Actuaries-Institute-June-2019.pdf

2 https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/politics/hike-in-super-savings-rate-to-barely-dent-pension-costs/news-story/baa4c28503254b399b006ff660fb71d0

3 Dawkins, J, 1992, Security in Retirement: Planning for Tomorrow Today, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra

4 https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-03/p2019-357183-TBVS-2018.pdf

5 We have assumed $100 for simplicity and note the problem is scalable (until new threshold are hit, or changes in the propensity to consume occur). This means, say a $1,000 contribution would likely have a similar impact at 10x the magnitude. We have assumed returns of 6.5% p.a. net of investment fees, wage inflation of 3.5%, and retirement at age 67. Tax on investment earnings of 9%. Values are given in today’s dollars deflated 3.5%.

6 https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2009/pdf/rdp2009-07.pdf