The ‘taper rate’ and retirement spending – what’s the connection?

- On 17/10/2019

- superannuation, taper rate

What is the ‘taper rate’ and when did it change?

The taper rate is part of the assets test used to determine eligibility for the Age Pension. Since 1 January 2017, a retiree’s annual pension is reduced by $78 for each $1,000 of assets above the relevant thresholds (before 2017, the taper rate was half that amount, at $39). From September 2019, the relevant assets test thresholds are set out in Table 1, with the Age Pension reducing to zero when the value of assessable assets exceeds the upper thresholds (noting that some assets are excluded from the assets test, such as a person’s main residence).

At the time of the change to the taper rate in 2017, the lower thresholds were increased by more than 30% which, according to the government meant that more than 50,000 part-pensioners would become eligible for a full pension for the first time. As the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) system matures, more and more people are expected to retire with higher superannuation balances and as a result of this change are expected to lose a higher amount of pension.

.

How does the taper rate impact retirees?

To understand its impact, let’s look at some cameos for a worker on average annual earnings of $90,000 and compare the results for a superannuation contribution rate of 9.5% versus 12% (ie. an additional 2.5%) paid over 40 years to age 67. Based on a marginal tax rate of 32.5%, if fully offset or sacrificed, the person’s net take home pay would reduce by about $61,000 over the 40 years.

For the purpose of this cameo, let us assume that the increase in SG from 9.5% to 12% will not lead to any increase in national personal income and corresponding reduction in company profits¹. We will also assume that the retiree spends all of their pension drawdown each year.

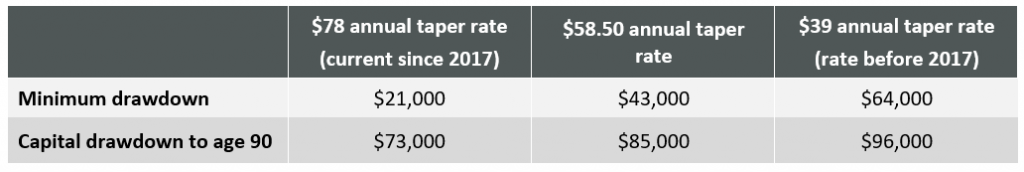

Following retirement at age 67, if the retiree is a single non-homeowner and draws down the minimum amount over 23 years to age 90, then the increased income produced by the additional savings is partially offset by a reduction in the Age Pension as set out in Table 2. On the other hand, if the retiree draws down their capital over the 23 years to age 90, they not only gain the benefit of spending more of their savings but also become eligible for higher Age Pension payments sooner.

Table 2. Accumulated increase in annual retirement income over 23 years to age 90

As Table 2 shows, if the retiree draws down the minimum amount each year, the annual taper rate would need to be close to $39 for the retiree to receive total payments higher than the accumulated reduction in the person’s net take home pay of $61,000. The retiree would be in fact be better off under a $78 annual taper rate if he/she also gradually draw down all their capital by age 90. In this scenario, the retiree’s overall net benefit would further improve with the lower taper rates.

.

So why don’t retirees typically draw down much more than the minimum?

There have been numerous studies, including one by CSIRO-Monash Superannuation Research Cluster, which indicate that most retirees in their 60s and 70s draw down on their account based pension (ABP) at modest rates, close to the minimum amount each year (which is 5% of their account balance for those aged 65 to 74). This behaviour will result in them living an unnecessarily modest retirement, many behaving as if they are in poverty.

There have been many reasons proposed for why retirees behave this way, among them a fear of running out of money and uncertainty about how long they will live. Some might also want to leave the home as a bequest, so they don’t consider using the equity in their residence. Hence they try to manage their own longevity risk by spending cautiously.

.

Is there a way we can give retirees the confidence to draw down more of their savings?

Since the early 1970s, the life expectancy of the average 65 year old has increased from about 12-13 years to 20 years for men and 22 years for women. But longevity is not uniform, it also varies considerably from person to person, so some form of longevity protection will be helpful for many Australians.

While the Age Pension is likely to provide enough certain lifetime income for low balance members, and high balance members won’t necessarily need to draw on as much of their capital anyway, the high proportion of Australians in the middle (with balances between say $300,000 and $800,000) could benefit greatly from more certainty for more of their retirement income.

In February this year, legislation was passed to amend the means test rules that will apply to longevity protection products from 1 July 2019. Under the new rules, only 60% of the purchase amount of a lifetime income stream will be an assessable asset and only 60% of the payments will be income for the means tests.

These regulatory changes should, in time, promote the development of new longevity protection products such as deferred lifetime annuities (DLAs) or deferred group self-annuitisation (GSA) products which should help retirees plan their retirement spending with more confidence.

.

How do DLAs and the new means test rules help?

Consider a person who is a homeowner and retires at age 67 with a superannuation account balance of $500,000 and uses $50,000 to purchase a DLA. At the date of purchase, the life expectancy of a 67 year old male is 18 years (ie. age 85). However, in our scenario, the DLA does not start making payments until age 87.

Under the income test, only 60 per cent of the payments from the DLA are assessed as income. However, no income is assessed at all until payments commence at age 87. Under the assets test, 60 per cent of the purchase amount (ie. $30,000) is assessed as an asset from the date of purchase for 18 years (ie. to age 85), after which point only 30 per cent of the purchase amount (ie. $15,000) is assessed as an asset.

With $20,000 less counting for the assets test, this person will be entitled to $1,560 p.a. more in Age Pension payments until their assessable assets falls below the lower threshold of $263,250 (or until age 85 if earlier). With a small amount of other assessable assets (say $30,000), if this person invested the remaining $450,000 in an ABP and withdrew the minimum amount each year, they would be eligible to receive the additional Age Pension payments for about 10 years (ie. to age 77) and they will accumulate to approximately $15,600 extra payments.

.

The confidence to spend

Longevity risk is one of the major risks faced by retirees. As mentioned earlier, the fear of running out of money and the uncertainty about how long they will live cause many retirees to try and manage their own longevity risk by spending cautiously. In addition to its means test benefits, a DLA partially solves that problem by providing a guaranteed amount of income for life once payments commence. This allows the retiree to more safely draw down the remainder of their savings up to that point, thereby enjoying a lifestyle that is better than would otherwise be the case during the early and more active years of retirement.

One of the problems facing retirees is the complexity around means-tests. It is impossible for the lay person to know how much to withdraw and when a DLA might be a suitable product given their circumstances. We need to find a way to deliver appropriate advice cost-effectively to help the growing number of people entering retirement and facing these problems

¹ We note many commentators have provided evidence that this assumption is unlikely, though it is useful to take this assumption for simplicity for this cameo.