Should the Superannuation Guarantee move to 12%?

- On 13/11/2018

- age pension, superannuation

Another publicity-grab for Grattan

In November 2018, the Grattan Institute released its latest report “Money in retirement: More than enough”. This is another in a series of Grattan reports attacking the foundations of the superannuation industry. It has modelled that the average Australian will have retirement income of at least 91% of their pre-retirement income. Based on this, it has made several recommendations including:

- Freezing the Superannuation Guarantee at 9.5%.

- Increasing the eligibility age for the Age Pension to 70.

- Increasing rent assistance to pensioners by 40%.

- Adjusting the means test taper rate, and including the family home in the means test.

- Drastically limiting the contributions that could be made to superannuation, and taxing all earnings in retirement.

- Other aged-based tax reforms.

Unfortunately, this research piece makes several policy recommendations which do not follow from the analysis conducted.

The biggest weakness in its analysis is that it relies on a series of ‘representative’ cameos of individuals. Unfortunately, taking a 30-year-old single homeowner and projecting through to their death at age 92 is simplistic and cannot be extrapolated to the whole population. This is compounded by overstating future retirement income by discounting it to today’s dollars at the Consumer Price Index rather than the industry standard of wage inflation.

Grattan also glosses over several important facts, which impact greatly on retirement adequacy and cannot be modelled using its individual cameos:

- 70% of retirees are married at retirement.

- There will be shift to lower home ownership over time.

- We have a large population of migrants, who enter the Australian workforce later in life.

- There are large amounts of investments held by older Australians – but these are concentrated amongst the wealthy and are not spread uniformly amongst the community.

- There are potential changes in work patterns through the ‘gig economy’.

- Whilst there are higher workforce participation rates for those over age 60 compared to even ten years ago, these rates still drop dramatically well before age 70.

Grattan also fails to understand the significance of the May 2016 Budget changes which led to much better equity in the system. In our opinion, its suggestion to drop the level of concessional deductible contributions to $11,000 a year is both provocative and ill-considered.

Balancing fiscal factors

While we are used to annual changes in public policy based on short-term fiscal measures (to balance government Budgets), major policy changes need to consider equity between all members and retirees today as well equity between generations. Consequently, it is nonsensical to compare this year’s tax concessions against this year’s Age Pension costs, though this is a common error made by economists and is often reported in the media.

Most industry commentators adopt good ideas, but they don’t look at the long-term costs of any change. Proper policy development requires the careful integration of tax concessions, social security benefits (primarily the Age Pension), superannuation benefits, part-time work in retirement and releasing equity in the family home (perhaps to pay for aged care late in life). To the extent that superannuation is deferred pay, it should be acceptable for retirees to earmark some of their retirement benefit towards a bequest on their death.

We are aware of the difficulties of measuring these trends given the large number of variables, the range of outcomes and the long-term time horizons. Sometimes, explaining them is even more difficult!

Objective of the Age Pension

Before considering how much people will need in retirement, we must first determine the role of the Age Pension, both today and in future. The government’s proposed objective of superannuation (to provide income in retirement to substitute or supplement the Age Pension) was accepted from the FSI Inquiry four years ago but has not yet been legislated. We consider there should also be an objective for the Age Pension itself as we have never settled on the right level of pension payments nor the fairest way to apply means-testing.

For those with modest retirement benefits, the Age Pension will provide an adequate safety net in retirement. The present value of the benefit rises each year due to increases in longevity and indexation to wages. In fact, the value of pension receipts for a couple retiring today will, on average, be more than $800,000. And herein lies the problem with integrating social security with superannuation. Means-testing whittles this away for those who are good savers and it is difficult to plan for retirement for the large body of members who start their retirement as a part Age Pensioner.

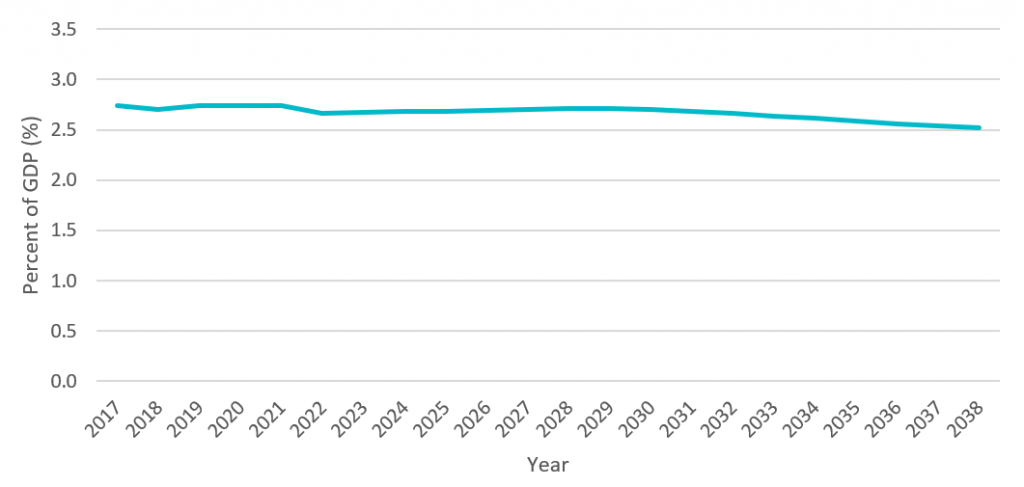

Rice Warner has the only private sector model (developed in conjunction with ISA) which looks at deciles of income, wealth, superannuation balances and homeownership, projected forward with both short term fiscal values and long-term outcomes. We used this for the The Age Pension in the 21st Century¹ paper prepared by Michael Rice for the Actuaries Institute’s 2018 Financial Services Forum, and were the first to publicise that the superannuation system is working well – the Age Pension costs, expressed as a percentage of GDP, have declined in the last decade and will continue to decline in future. This has been caused by the large real earnings of superannuation funds over long-periods (based on high levels of growth assets) as well as the January 2017 changes to the means-test (which were introduced to balance the Budget rather than as part of a long-term strategy).

Our modelling shows that projected Age Pension expenditure will continue to decline relative to GDP (Graph 1), and this gives opportunities for the government to pay for other benefits for retirees, including an increase in public sector housing, subsidies to build aged care facilities, rental assistance for those in private sector housing and more generous means-testing. It has already allowed the government to withdraw from its policy of increasing the eligibility age for the Age Pension to 70 by 2035.

We also believe inequities in the system can be addressed. For example, it does make sense to include the family home into the means- test, but that should be done scientifically. First, make the change for those retiring in fifteen years, so it is not retrospective to today’s retirees and those approaching retirement – then, people can plan their retirement in good time. Second, use the reduced Age Pension costs to change the system, including higher base pensions, changes to means-test thresholds and improved rental assistance. In other words, don’t steal the reduced Age Pension benefits, but model a full package with better targeting towards those in need.

Graph 1. Projected Age Pension expenditure (percent of GDP)

Should the Superannuation Guarantee rise to 12%?

If there were no Age Pension, there would be a good argument to have minimum savings of 15% of salary or more. However, the means-tests on the Age Pension complicate the value of any increase in Superannuation Guarantee (SG). For many, the higher superannuation benefit will be largely offset by a reduced Age Pension, at least for the first decade or so of retirement. Despite this hidden tax, there are good strategic reasons to increase the SG:

- If the superannuation system can continue to deliver strong real returns over decades, this is better than most people will be able to achieve with their own savings.

- The fixed costs of the industry allow the additional contributions to deliver even better value (as fees will fall as a percentage of balances as cash flow grows).

- The higher superannuation benefits will lead to even lower government benefits, which will give scope to redirect expenditure to areas of need (not necessarily just to retirees).

The first 9% of the SG was introduced at a time when real wages were rising. There is an argument for timing any future increases in similar economic conditions or potentially excluding lower income people because the extra income is worth more to them now. Further, the impact of a higher SG contribution will not be noticeable for many years. It will have most impact on those starting their working life on 12% and they will not retire for at least 40 years.

Ultimately, good policy needs to incorporate the long term strategic aims and purpose of the SG. That is, to reduce reliance on the Age Pension. The complexity of interactions between the different retirement pillars makes it difficult to evaluate the value in increasing the SG and simple cameos are not up to the task.

The key is to ensure we all agree on the objectives of superannuation and of the Age Pension itself. In doing so, we can then ensure that policy proposals are consistent and promote the wellbeing of all Australians.

¹ https://www.ricewarner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/The-Age-Pension-in-the-21st-century-220518.pdf